Researchers Have Found That Family Management Practices Are Positively Related to

- Inquiry

- Open Access

- Published:

How do work-family balance practices affect work-family unit conflict? The differential roles of work stress

Frontiers of Business Enquiry in China volume eleven, Commodity number:8 (2017) Cite this article

Abstruse

This paper investigates the relationship between employees' perception of work-family balance practices and work-family conflicts. It examines the office of challenge stress and hindrance stress as moderators. Based on survey data collected from 841 civil servants in Beijing, we found that perceived piece of work-family unit balance practices may reduce work-family conflict, while claiming and hindrance work stresses were positively related to work-family disharmonize. In addition, challenge and hindrance stresses differentially moderated the relationship between perceived piece of work-family practices and work-family conflict. When challenge stress is loftier then work-family unit residual practices will reduce work-family unit conflict. Nevertheless, under loftier hindrance stress, work-family residual practices will serve to reduce work-family disharmonize less. More detailed analysis of the configurational dimensions of work-family remainder practices (work flexibility, and employee and family wellness care) are as well tested. This report provides additional insight into the direction of work-family interfaces and offers ideas for time to come research.

Introduction

In recent decades individuals accept experienced increasing levels of job demands and job stress due to broadened job scopes. Increased task responsibilities and extended work hours go more than common in the workplace. In the meantime, changes have likewise occurred in the family―there are more dual career and single parent families, likewise equally more working adults who are caring for both the elder and younger generations (Neal and Hammer, 2007). Researchers have responded to these trends by investigating piece of work-family or work-family interfaces to sympathize the factors that may influence or be influenced by work-family balance. Nonetheless, this line of inquiry has employed different terminologies, levels, and approaches (Maertz and Boyar, 2011).

Inquiry at the individual level, on the one hand, has focused on the constructs of work-family or family-work conflicts/enrichment/facilitation to investigate their antecedents and outcomes (Allen et al. 2012; Byron, 2005; Frone et al. 1992; Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985; Kinnunen and Mauno, 1998; Premeaux et al. 2007). On the other paw, research at the organizational level has focused on the influence of work-family practices/policies on organizations. These studies consider a serial of piece of work-family practices every bit HRM bundles—using different terms such as family unit-friendly workplace practices (FFWP), work-family unit programs, and work-family human resource bundles (e.m. Bloom et al. 2011; Beauregard and Henry, 2009; Konrad and Mangel, 2000; Perry-Smith and Blum, 2000). Others mainly focus on special practice areas such every bit flextime, telework (due east.g. Lapierre and Allen, 2006; Madsen, 2003), dependents care (e.g., Berg, et al., 2003), and the positive influence of the practices mentioned above are mostly supported. However, efforts to integrate piece of work-family practices and employee work-family disharmonize accept been thin.

A closer examination of the empirical literature reveals that work-family unit residue practices may not always alleviate employee work-family unit conflict (Kelly et al. 2008). For example, while some studies found significant negative relationships between work-family balance practices and work-family unit conflict (O'Driscoll et al., 2003; Thompson et al. 1999), others found meaning positive relationships (Brough et al. 2005; Hammer et al., 2005) or non-pregnant relationships (Kossek et al. 2006; Lapierre and Allen, 2006). These inconsistencies in previous research findings suggest that the existing conceptualizations of how work-family unit balance practices influence work-family disharmonize may exist scarce. Some researchers have constitute that i explanation of this inconsistency might originate from the "agency and capabilities gap" (Hobson, 2014). They have also discovered that the extent of this gap was somehow dependent upon certain national policy frameworks, organizational/managerial support and the individual'due south preferences.

Thus, a principal goal of this research is to explain the inconsistent findings regarding the relationship betwixt piece of work-family balance practices and piece of work-family unit conflict. In their seminal review article, Kelly et al. (2008) suggest that previous research tended to vary in the measurement of work-family residuum practices. Some focused on 1 or two specific practices such as flextime, telework (east.thou. Lapierre and Allen, 2006; Madsen, 2003), and dependents intendance (e.k. Berg et al., 2003), while others examined multiple practices as predictors—such as family-friendly workplace practices (FFWP), work-family unit programs, and work-family human resources bundles (e.g. Bloom et al. 2011; Konrad and Mangel, 2000; Perry-Smith and Blum, 2000). In addition, while some previous studies take measured the adoption of piece of work-family practices, others focused on the implementation of such practices equally perceived by employees. Kelly et al. (2008) contend that measuring the perceived use of these practices is more meaningful because piece of work-family balance practices will exert an effect on work-family conflict only when they are actually used by employees.

Another possible explanation for the inconsistent findings is that the effectiveness of piece of work-family balance practices in easing work-family conflict depends on the types of stresses that are experienced by the employees. Researchers distinguish between stress that individuals perceive as rewarding (challenge stress) and stress that is viewed as constraining (hindrance stress). This is because these two types of stress are differentially associated with job attitudes and behavioral intentions (Cavanaugh et al., 2000). Despite evidence showing the effect of these two types of stress, there has been no attempt to integrate them with piece of work-family and work-family interfaces to explain the relationships between best practices and perceived piece of work-family conflict.

Edifice on conservation of resource (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989, Hobfoll and Freedy 1993), particularly from the resource edifice perspective, this paper intends to make full these gaps and brand several contributions to the literature. Kickoff, we introduce work-family unit rest practices as a series of managerial policy resource. In add-on, based on the literature and managerial practices, we construct and examine two specific dimensions of work-family unit balance practices through data analysis. These are workplace flexibility, which focuses on providing flexibility at work and enhancing job autonomy, such equally telecommuting, workplace flexibility, job autonomy (Leslie et al., 2012; Kossek et al. 2006; Shockley and Allen, 2007; Kahn et al., 1964, p. 19), and employee and family health care, that involves the economic and material resources of an employee and their family—such as insurance and allowances—that compensate employees for their devotion to their piece of work and the reduced time they spend with their family (Staines, 1980; Rothbard, 2001), thus preventing resources depletion (Premeaux et al. 2007). Based on these two dimensions, nosotros examined their differential relationships with work-family conflict, which contributes to a configurational perspective to elaborate the in-depth structures of work-family unit balance practices.

Secondly, instead of measuring the organizations' adoptions of work-family practices, we measure employee perceptions of the bodily employ of work-family practices. In the public sector, piece of work welfare practices account for a higher proportion of HRM systems (relatively) than that of firms, so the benefit policies themselves are well-nigh equal to employees in the public sector. This in turn allows us to capture how individual perceptions of those practices substantially vary. In fact, human resource management researchers have argued and shown that human resources management practices need to be perceived past employees to be translated into desirable outcomes (Liao et al. 2009). By introducing the context of the public sector and investigating individual perceptions of piece of work-family balance practices, this report also opens up an opportunity to examine individual moderators that may explain the differential effectiveness of piece of work-family practices in reducing employee work-family conflict.

Thirdly, previous studies adjustment individual differences with work-family conflict often focused on biographic factors, such as gender and marital status (i.e. Byron, 2005). In contrast to this, our report contributes by introducing work stress—peculiarly challenge and hindrance stress—into the model, and examines their moderation effects on the relationships between piece of work-family practices and work-family conflict.

Theory and hypotheses

Work-family disharmonize and resource edifice

Individuals play multiple roles in their lives; incompatibilities amid the roles tin can render full participation in one or more roles difficult (Kahn et al. 1964) and create work-family conflict. Work-family disharmonize is defined equally "a grade of interrole disharmonize in which the function force per unit area from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect" (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985, p. 77). Furthermore, part conflict is due to the limited resources of individuals (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985). Indeed, the emergence of piece of work-family unit conflict reflects the competition for express resource between a work office and a family function (Guest, 2002). Only a few studies, however, have investigated means of decreasing piece of work-family unit conflict through the lens of resource (Kelly et al., 2008)—specially through the view of conserving resources, known equally COR.

As COR theory suggests, individuals may ain or fight for resources like objects, conditions, personal characteristics and energies; they strive to retain, protect and build these valued resources. When faced with potential or actual loss of resources, they may feel worried (Hobfoll, 1989, Hobfoll and Freedy 1993). So, the essential fashion to decrease work-family unit conflict is to retain and protect current resources—too every bit to build and invest in future resources (Leslie et al., 2012; Hobfoll, 2001). Thus, the aspect of resource building is taken into consideration. As Kelly et al. country (Kelly et al. 2008; p. 310), work-family practices are deliberate organizational resources, targeting the work-family interface, which may play an of import role in reducing piece of work-family unit conflict and/or back up employees' lives outside of piece of work. Consequently, by introducing work-family rest practices into our model nosotros are able to decrease work-family disharmonize by fashion of resources-building.

Work-family balance practices and work-family conflict

Work-family conflict is associated with negative piece of work outcomes in organizations, so information technology is imperative that organizations should minimize their employees' piece of work-family conflicts. Many initiatives have been employed to decrease piece of work-family conflict, including job autonomy, supportive work-family unit culture, telecommuting, work flexibility (flextime and flexplace) and and so on (e.g. Premeaux et al. 2007; Kossek et al. 2006; Shockley and Allen, 2007; Hobson, 2014). By providing employees with valuable resources, piece of work-family unit balance practices are intended to reduce piece of work-family conflict. All the same, these practices often have mixed effects on work-family unit disharmonize, which are often influenced past family characteristics or individual differences—such every bit family support, the number or age of children (e.g. Premeaux et al., 2007; Drobnič and Leόn, 2014), and individual differences such as extraversion (Grzywacz and Marks, 2000).

Existing studies of work-family remainder practices are mostly focused on workplace flexibility (east.g. telecommuting, flextime and flexplace); withal, inconsistent results have been reported in the inquiry surroundings of the impact of working hours/time autonomy on work-family conflict. Some results acknowledge that work flexibility practices are negatively related to work-family unit disharmonize (Byron, 2005; Gajendran and Harrison, 2007; Shockley and Allen, 2007). However, there is also evidence from several previous studies that suggests that flexibility in working times that allows for autonomy and control over 1's footstep of work does not necessarily enhance the quality of 1's personal life (Lee and McCann, 2006; Smith et al., 2008; Hobson and Fahlen, 2009; Hobson, 2014).

Similarly, the effect of family-friendly benefits (e.grand. parental leave of absence, dependent childcare) on work-family conflict were as well mixed. For instance, Kossek and Ozeki (1998) did non discover the expected touch on that dependent care benefits exert on work-family conflict, while Goff et al. (1990) institute that on-site childcare lowered work-family conflict amidst working parents (Anderson et al. 2002). Except for the to a higher place studies focusing on a specific practice, other researchers treat work-family unit balance practices as a bundle for testing their impacts on firm productivity or organizational performance (de Bloom et al., 2010; Konrad and Mangel, 2000; Perry-Smith and Blum, 2000). For example, Family unit-Supportive Programs were advanced and used by many researchers (eastward.1000. Friedman, 1990; Friedman and Galinsiky, 1992; Kraut, 1990; Lewis, 1992; Thompson et al. 1992) which mainly consist of flextime, a compressed work week, job sharing, child care help, work at home, and reduced work hours. These items are largely consistent with previous research on dependent care benefits and work flexibility.

Although the two dimensions of work-family balance practices are dissimilar in their content, formats and effects, they ultimately act as essential resources provided by organizations. Equally mentioned above, role disharmonize takes identify when ane has full participation in one role, while ignoring another (Kahn et al. 1964). Indeed, the essence of part disharmonize is due to limited resources (Staines, 1980; Rothbard, 2001). In light of this, work-family balance practices, such as offering intendance for employees and family, can be seen as a kind of resources that compensates for a lack of family involvement. Work-family rest practices, like work flexibility, may promote flexible working, which may save ane's time or free energy resource, and compensate individuals for their family office.

Hypothesis ane. Employees' perception of work-family unit residuum practices will reduce work-family conflict.

Piece of work stress and work-family conflict

Stress is defined as "an individual'due south psychological response to a situation in which in that location is something at pale for the individual and where the situation taxes or exceeds the private's capacity or resource" (LePine et al. 2004, p. 883). Individuals at work perceive unlike types of stress. Some may derive from chore overload, fourth dimension pressure level, and added responsibilities that could provide challenges or opportunities for personal development and achievements; these are referred to equally challenge stress (Cavanaugh et al., 2000).

On the contrary, some stress originates from excessive or undesirable constraints that can produce obstacles to personal growth and accomplishment; these are divers as hindrance stress (Cavanaugh et al., 2000). According to Rothbard (2001) and Staines (1980), if one receives more than stress from work, then i cannot invest enough resources (east.g. energy and time) into one's family; this can lead to work-family unit disharmonize.

Although challenge and hindrance stress take been differentially related to piece of work attitudes and intentions—such equally chore satisfaction, organizational commitment, job search, and voluntary turnover (Cavanaugh et al., 2000; Podsakoff et al., 2007)—they are both positively related to burnout and higher levels of work-family disharmonize considering of added work demand (east.g. Lepine et al., 2004; Voydanoff, 2005a,b; Scherer and Steiber, 2009; Valcour, 2007; Schieman et al., 2009; Steiber, 2009; Beham and Drobnič, 2010; den Dulk et al., 2011). Podsakoff et al. (2007) also found in their meta-assay of previous research that both challenge and hindrance stressors were positively associated with strain, which may render information technology very difficult for individuals to invest resources in family successfully. This suggests that the direct furnishings of both challenge and hindrance stress on work-family conflict would be positive.

Hypothesis 2. Challenge and hindrance stress will accentuate piece of work-family disharmonize.

Challenge and hindrance stress every bit moderators

Although claiming and hindrance stress have been shown to be related to certain job attitudes and intentions in differing ways, no attempt has been made to integrate them with relationships between piece of work-family rest practices and work-family conflict. When faced with potential or bodily loss of resources in work, individuals with unlike kinds of stresses may experience opposite emotions, equally well as distinct evaluations; this may influence how they react to those situational cues. Every bit a result, stresses may moderate the effects of how individuals receive and make use of work-family residuum practices to reduce their work-family conflict.

Challenge stress has a certain positive effect on individual attitudes and behaviors. Equally Cavanaugh et al. (2000) and Selye (1976) suggest, claiming stress is favorable for private development, making a person more than willing to positively evaluate work and tasks―also equally organizational practices (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). More than to the bespeak, stresses that come from time, workload and responsibility can arouse the desire for challenges and achievements, which may convey adept spirits and emotions (Weiss and Cropanzano, 1996). To summarize, challenge stress guides individuals into positive evaluations and emotions; thus it is positively related to motivation (Lepine et al., 2004). As we know, individuals are afraid of losing resources―they may endeavour their best to avoid potential and actual loss of resources (Hobfoll, 1989). Therefore, promoted past challenge stress, individuals are more willing to invest in resources and to apply existing piece of work-family balance practices that actively increase work resources and family resources. With more than resource, individuals may find it easier to fulfill their evolution and to reduce work-family conflict.

On the contrary, hindrance stress prevents individuals from working hard to reach their goals because, due to various constraints, the goals are considered unachievable (Lepine et al., 2004). They may believe that efforts to alter the status quo are non worthwhile―thus they make fewer attempts to use the organizational resource provided by work-family unit balance practices to reduce work-family conflict. In improver, hindrance stress may inspire negative emotions, making them respond passively to piece of work and life. They might avoid changes, and stay on alert to risks from outside (Lepine et al., 2005), which may also decrease their utilization of organizational resources.

Thus, we advise that:

Hypothesis 3. Claiming stress will strengthen the relationship between employees' perception of work-family residue practices and work-family disharmonize so that, when challenge stress is loftier, work-family balance practices will reduce work-family conflict more than than when challenge stress is low.

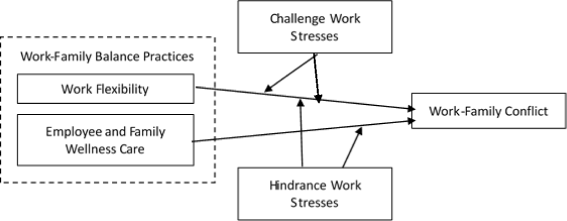

Hypothesis 4. Hindrance stress will weaken the relationship betwixt employees' perception of piece of work-family balance practices and work-family conflict so that, when hindrance stress is high, work-family unit remainder practices volition reduce work-family conflict less than when claiming stress is low (Fig. i).

Conceptual model

Methods

Sample and data collection

In 2014 we sent surveys to ane,000 public sector civil servants in Beijing, China. 841 respondents fully participated in this current study, leading to a response rate of 84.one%. Ceremonious servants are an appropriate sample for this study for the following reasons. Firstly, in China, piece of work-family unit residual welfare practices for civil servants are abundant when compared with employees in the industrial sectors, which made the research cover more sufficiently piece of work-family rest practices. Secondly, governments tend to prefer relatively consistent work-family unit benefits across unlike categories of ceremonious servants. Therefore, variations in employee reporting of piece of work-family unit residue practices may reflect individual perceptions of the bodily implementation of these practices―rather than the difference in the adoption of practices. 58.3% of the respondents were men, 47.6% were between 41 and 50 years old, most had a Bachelor's degree (78.4%), and almost all were married (94.four%). Moreover, a large proportion of the respondents had been a civil servant for 21–xxx years (45%) and had been at their section-level position for less than four years (62.2%).

Measures

Perception of work-family balance practices

To measure the perception of work-family residue practices, we integrated the measures used in several prior studies (Flower et al. 2006; Kelly et al., 2008; Konrad and Mangel, 2000; Perry-Smith and Blum, 2000; Leslie et al., 2012), likewise as the best practices suggested past the Alliance for Work-family Progress. We came up with 10 items. These include practices related to improving piece of work flexibility, proactive health and wellness approaches, also as benefits and back up provided to families. We measured the extent to which each item was implemented in the organizations using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (to a very piffling extent) to 5 (to a great extent). We conducted exploratory cistron assay (EFA) to explore the dimensional structures of these items; the results are shown in Table 1.

The EFA Results show that perceived piece of work-family rest practices fall into 2 factors. The get-go included half dozen items which could exist interpreted as wellness and benefits for both employees and their families, such every bit providing supplemental insurance or medical services to both employee and their dependents (child or elderberry). These practices focus on the direct and economic benefits of employees and their family unit members; we proper noun this factor employee and family wellness intendance. The second cistron consists of four items that focus on time-related or location-related benefits of flexibility such equally responsive piece of work shifts, flextime, paid holidays and telecommuting; nosotros proper noun this indirect and non-economic work-family unit residual practice as work flexibility. The Cronbach'due south alphas for cistron one and factor 2 are .82 and .79, respectively.

To confirm the rationality of the two dimensions mentioned above, nosotros conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (as shown in Table 2), which shows small back up for our two-factor model: χ ii (34, N = 841) = 275.58, p <.001, comparative fit index (CFI) = .96, and non-normed fit index (NNFI) = .95 (Bentler and Bonett, 1980). The factor-loadings of the ten items are all greater than .v; the value of the boilerplate variance extracted (AVE) are .57 and .68 respectively for the two factors. We therefore adopted these two factors and formally named them as employee and family wellness care and work flexibility in the post-obit analyses.

Challenge and hindrance stress

We adapted x items adult by Cavanaugh et al. (2000) and LePine et al. (2004) to measure out challenge and hindrance stress. The five claiming stress items include "the amount of time I spend at work", "my work is challenging", "the number of projects and or assignments I take", "the volume of work that must exist accomplished in the allotted time", "the amount of responsibility I have", and "time pressure I experience". The five hindrance stress items are "the degree to which politics rather than performance affects organizational decisions", "the corporeality of red tape I need to get through to get my job done", "the inability to clearly understand what is expected of me on the job", "the lack of job security I have", and "the degree to which my career seems 'stalled'". We used the Likert calibration with response options ranging from one (to a very little extent) to 5 (to a neat extent). The Cronbach's alpha for challenge and hindrance stress are. 78 and .55.

We further performed confirmatory gene analysis to validate the stress measures' convergent validity and discriminant validity and obtained pocket-size fit indices (Table 2), χ 2 (thirteen, N = 841) = 116.39, p <.001, CFI = .92, NNFI = .87 (Bentler and Bonett, 1980). In addition, the factor-loading of about of the items are greater than .five; only two of them are just below .v. In terms of Bagozzi and Yi (1988, 1998)'s suggested criteria (AVE ≥ .50), although the AVE value of the hindrance stress is .36, which is below .5, the AVE value of challenge stress is.57, which is acceptable.

Work-family disharmonize

To measure work interference with family unit (WIF), we adopted ix items adult past Carlson et al. (2000), which distinguishes betwixt three dimensions of WIF: time-based, strain-based, and behavior-based WIF. We use a scale with response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly hold). The Cronbach's blastoff is .95.

A confirmatory factor analysis of the measures bear witness (Table 2) that all the three factors had good convergent validity and discriminant validity: χ 2 (24, N = 841) =239.43, p <0.001, CFI = .98, NNFI = .97 (Bentler and Bonett, 1980), and the gene-loadings of the 10 items are all greater than five. In improver, the AVE of the three factors are all greater than .5 (AVE = .98, .96, and .87, respectively). The correlation coefficients betwixt latent variables are quite moderate, and their squares are smaller than the relevant value of AVE.

Control variables

Based on previous research on the effects of work-family programs and the antecedents of work-family disharmonize, in that location are other explanations for the differences in WIF. Consequently, nosotros adopted the post-obit demographic characteristics as control variables.

Gender.

Though the relationship between gender and work-family conflict is non consequent in previous meta-analyses (Allen et al. 2000; Byron, 2005), gender may play a role in influencing the relationship between perceived work-family rest practices and work-family unit conflict. As previous studies suggest that firms employing a larger percentage of women develop more all-encompassing work-family programs (Konrad and Mangel, 2000), females may benefit from work-family unit balance programs that reduce work-family conflict more than males.

Didactics.

Education may likewise influence how individuals react to work-family residual practices. Highly educated individuals may expect to be valued past the organization. Constructive work-family rest practices can be seen as a symbolic ways to value employees (Pfeffer 1981). Thus, nosotros included "instruction" equally a control variable.

Marital condition and age.

Married individuals and middle age individuals may have more family responsibilities than unmarried ones (due east.g. caring for children and elderly), so we included marital status and age equally command variables.

Tenure.

Information technology is possible that work-family conflict may accrue the longer an individual works. Thus, nosotros too control for "tenure".

Results

Table three reports the descriptive statistics (including means and standard deviations of all the variables) and correlations between variables. We establish that the iii dimensions of work-family conflict―time-based piece of work family conflict, strain-based piece of work family conflict, and behavior-based work family conflict―are all significantly and negatively related to the perception of piece of work-family balance practices, "employee and family unit care" and "work flexibility" (p <.01). Moreover, both challenge and hindrance stresses are basically and positively related to 3 kinds of piece of work-family disharmonize (p <.01).

Tables four, v and 6 nowadays the regression results predicting time-based, strain-based, and beliefs-based work-family disharmonize, respectively. We used one-tailed tests to evaluate the significance of the predicted effects, given that one-tailed tests are suitable for directional hypotheses (Pelled et al. 1999). According to Hypothesis one, we expected that piece of work-family unit rest practices would be negatively associated with the iii dimensions of work-family conflict, which received partial support as shown in Model ii of the tables. The 2 configurational dimensions of work-family residual practices present differential effects. Employee and family wellness care have a slim and positive impact on piece of work-family conflict, while work flexibility is consistently and negatively related to time-based, strain-based, and behavior-based work-family conflict.

We besides hypothesized that both challenge and hindrance stress would exist positively associated with three types of work-family conflict (Hypothesis two), which received full support: both challenge and hindrance stress are consistently and positively related to all 3 types of piece of work-family conflict.

To examination the moderation between work-family unit balance practices, and challenge stress (Hypothesis 3) or hindrance stress (Hypothesis iv), nosotros entered their interactions in Models 3 to 5. We centralized all the independent and dependent variables in the regression models to avert multicollinearity between interaction terms and their individual components (Aiken and Westward, 1991). We entered the interaction terms for each dimension of the work-family balance practices in Model 3 and Model 4. In Model v, we included all the interactions terms together. The results testify that work stress has meaning moderation effects on the relationship of work-family balance practices and piece of work-family unit conflict; moreover, unlike work stresses (challenge vs. hindrance stress) display dissimilar moderating effects on the human relationship. The moderation of each piece of work stress on different configurational dimensions of work-family unit balance practices ("employee and family care" and "work flexibility") are, nonetheless, fairly consistent.

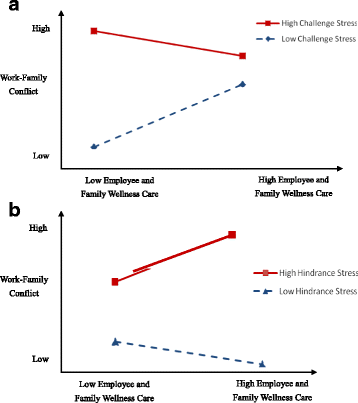

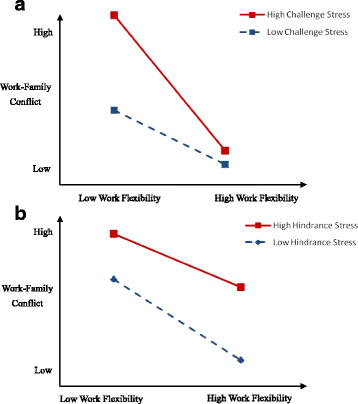

Additionally, beyond Tables 4, 5 and 6, the moderation models with the same predictors and number (from Model three to Model v) are also quietly consistent across different dependent variables (fourth dimension-based, strain-based and behavior-based work-family conflicts). As a outcome, nosotros drew the figures (Figs. 2a and b, 3a and b) to respectively illustrate the converging trend of moderating furnishings with the same predictors on general work-family conflict.

a. The moderating consequence of challenge stress on "employee and family health care" and work-family conflict. b. The moderating issue of hindrance stress on "employee and family health care" and work-family conflict

a. The moderating consequence of claiming stress on "work flexibility" and piece of work family conflict. b. The moderating effect of hindrance stress on "piece of work flexibility" and work-family disharmonize

In Model 3 of each regression (Tables 4, 5 and vi), the interaction between employee and family wellness care, and challenge stress are significantly and positively related to piece of work-family unit conflict (β = −.13, −.1, and -.07; p <. 001, p <.001, p <.05; ΔRii = .02,.01,.01, respectively). Figure 2a illustrates the nature of interaction between care and challenge stress on work-family conflict. Individuals with high challenge stress experience a stronger decrease of piece of work-family disharmonize when they perceive more care for themselves and their family than individuals with low challenge stress. This provides support for Hypothesis three, which expected that challenge stress can heighten the attenuating upshot of work-family unit balance practices on piece of work-family conflict.

The interactions between piece of work flexibility and challenge stress are shown in Model four of each regression, which are significantly and negatively related to work-family unit conflict (β = −.xi, p <.001; β = −.05, p <.05; and β = −.06; p <.05; ΔR2 = .01,.00, and .00, respectively). Effigy 3a shows the positive interaction between work flexibility and challenge stress on work-family conflict. When individuals experience high challenge stress, the relation between work flexibility and work-family conflict is more negative than when individuals perceive depression claiming stress. This once again provides support for Hypothesis three.

Model three of each regression (Tables 4, 5 and 6) shows the interactions between "employee and family unit care" and hindrance stress. The interactions are strongly and negatively related to work-family conflict (β = .11,.09, and.1; p <.001; ΔRtwo = 0.02, 0.01, and 0.01, respectively). Figure 2b shows the reversing nature of interaction between "employee and family unit intendance" and hindrance stress on work-family disharmonize. It shows that when hindrance stress varies from low to high, "employee and family care" volition accentuate work-family conflict. This indicates the more sensitive moderation consequence of hindrance stress on the human relationship between "employee and family intendance" and work-family conflict. With high hindrance stress, high levels of employee and family wellness care will increase work-family unit conflict. This finding supports and goes further than Hypothesis 4. This predicted that the moderation of hindrance stress would no longer reduce the negative impact of employee and family wellness care on work-family conflict, just would accelerate employee and family health care to increase work-family disharmonize.

In addition, the interactions between work flexibility and hindrance stress on piece of work-family unit conflict are also significant (β = .07,.07, and.1; p <.05, p <.05, p <.01; ΔR2 = .01,.00, and.00, respectively). Figure 3b illustrates the negative interaction between work flexibility and hindrance stress on work-family conflict. Compared with low hindrance stress, work flexibility contributes less to the reduction of work-family conflict when hindrance stress is high. This, again, supports Hypothesis 4, which predicted that hindrance stress would reduce the negative relationship between work flexibility and piece of work-family conflict.

Discussion

Theoretical implications

The results of the present inquiry make a few contributions to the literature. Firstly, the results demonstrate the link between employees' perception of work-family practices and work-family conflict. Previously, inquiry on work-family interfaces tended to have two approaches: on the one mitt, human being resource management literature focused on the relationship between piece of work-family practices and organizational performance; on the other manus, organizational behavior researchers studied more than extensively the individual antecedents and consequences of piece of work-family conflict.

However, there has been little research on the linkage between work-family residue practices and work-family conflict (Kelly et al., 2008). Different the general perspective of resource loss in COR, our research is based upon the perspective of resources building. By combining organizational management resources with individual resources, our written report focuses on the effect of the perception of work-family practices in reinforcing individual resource so equally to reduce employee piece of work-family conflict. This written report achieves the integration of the HRM field, work-family unit interface and COR theory.

Secondly, based on COR, we farther analyzed organizational resources, and divided work-family balance practices into two dimensional factors. Previous inquiry has either treated piece of work-family practices as a bundle, or focused on just one or two specific practices. For example, Perry-Smith and Blum (2000) studied "work-family unit human resource bundles", and Christensen and Staines (1990) focused on flextime and examined whether it was a viable solution to work-family unit conflict. Our factor analyses identify two specific dimensions of work-family balance practices: "employee and family wellness care (cloth resources)" and "work flexibility (non-material resource)".

Both of these dimensions have generated informative results regarding their relationships with piece of work-family unit conflict. Specifically, nosotros found that work flexibility demonstrated a consistent and significant effect in reducing employee fourth dimension-based, strained-based, and behavior-based piece of work-family conflict, whereas the consequence of employee and dependent intendance was not meaning. Flexibility-related piece of work-family balance practices may be most effective because they tin help reduce the competition of resources between work and family life, and ensure individuals' resources are invested in family life. Obviously, according to the results, unlike types of resources-edifice may vary in their reduction of piece of work-family unit conflict, and non-material resources take been demonstrated to accept a more intrinsic and significant impact.

Thirdly, according to COR, losing resources is closely related to individual stress. Therefore, we examined work stress equally moderators betwixt work-family balance practices and work-family unit conflict, uncovering how the effectiveness of work-family residue practices may depend on the degree to which individuals experience challenge or hindrance stress. Previous studies that investigated the moderations betwixt work-family practices and work-family conflict tended to focus on organizational characteristics or individual demographics, while efforts to examine individual work contexts have been sparse. Although previous research has suggested that challenge stress and hindrance stress are differentially related to employee work attitudes and intentions (Cavanaugh et al., 2000; LePine et al., 2004), our results suggest that, every bit both types of stress crave individuals to invest more resources at work, both increased employee work-family unit conflict.

Furthermore, challenge and hindrance stress differentially influence how individuals utilize piece of work-family unit residue practices to reduce piece of work-family conflict. When individuals feel high challenge stress, the furnishings of work-family residual practices in reducing employee time-based, strain-based and behavior-based work-family conflict were more prominent than when individuals experienced depression challenge stress. On the reverse, when individuals experienced loftier hindrance stress comparing to depression hindrance stress, the power of work-family unit balance practices became weaker in reducing employee work-family conflict, or farther increased work-family unit conflict when it came to employee and family intendance. This suggests that high claiming stress may enable individuals to actively seek intervention (employer provided piece of work flexibility and employee and dependent care) to change the status quo (reduce work-family conflict).

Nonetheless, high hindrance stress developed past perceived constraints at work may cultivate a "learned helplessness" in individuals, which prevents them from effectively utilizing piece of work-family residual practices to alleviate their piece of work-family conflict. These results provide additional insight into understanding the relationships among stress, work-family unit practices and work-family conflict.

Managerial implications

Existing research on work-family balance practices and piece of work-family conflict has mainly focused on Western countries. For many years, there have been well-established policies and practices in both government and private sector organizations aimed at addressing work-family residue. Moreover, employees in these nations prioritize piece of work-family balance when considering their pick of task and workplace (Hobson, 2014). However, it is simply in recent years that Chinese researchers accept started to work in this field. Besides the theoretical implications, our report results also offering several managerial implications for organizations striving to minimize employee work-family disharmonize through utilizing work-family balance practices effectively and economically.

We found that work flexibility had a more salient effect on employee work-family unit conflict than providing intendance to both employees and their family unit. This provides implications for managers contemplating the virtually constructive interventions to reduce employee work-family unit conflict. With express resources, managers may try to enhance work flexibility, so that the office conflicts between employee work and life could be nearly effectively reduced.

Even so, although employee and family unit wellness care provides additional fiscal resources for employees to take care of dependents, information technology does not fundamentally tackle the disharmonize between an employee's work and life. It could be because employees with family unit-friendly caring benefits may exist less considerate of their families while putting more effort into their jobs, which might lead to ineffectiveness and fifty-fifty the opposite effect of "employee and family care" practices.

In addition, our findings of the moderation of stress on the relationship between perceived work-family practices and work-family conflict provide an additional insight for managers striving to maximize their return on investments in work-family residuum practices. Truthfully, the findings of this enquiry are somewhat counter-intuitive. Specifically, enhancing employee challenge stress by optimizing job blueprint and evolution opportunities tin can cultivate a sense of confidence in employees, which will augment their receptiveness to work-family residue practices. Likewise, reducing hindrance stress by removing constraints and obstacles at work likewise helps employees to effectively utilise piece of work-family balance practices to manage their work-family conflict.

Limitations and futurity extensions

The study results should exist interpreted in the light of several limitations. One of the limitations is the potential common method variance in the measurements. Although nosotros measured the perception of work-family practices and work-family conflict at the individual level, equally perceived by employees, employees are indeed the best informants of the actual work-family practices in use, and their ain piece of work-family unit disharmonize. In addition, to minimize the common variance, we tested the discriminant validity of the independent and dependent variables in the same measure out model. All the variables' square of correlation coefficients was smaller than the corresponding AVE, which provide small-scale support for the discriminant validity of the variables. Thus, common variance may not have caused the differences in the concluding results (Conway and Lance, 2010). That existence said, we call for more studies in the future to use cantankerous-level analysis in gild to understand the piece of work-family interface.

In addition, although we have attempted to clarify the internal structure of work-family practices and identified the two factors of "employee and family health care" and "piece of work flexibility", the field of piece of work-family unit practices will nevertheless benefit from a more consistent conceptualization of the constructs. The terms used in the previous research have included "FFWP" and "piece of work-family programs" (e.g. de Flower et al., 2010; Konrad and Mangel, 2000). Nosotros urge future research to form a more than synthetic and clear definition for "piece of work-family practices".

Finally, testing the hypotheses in the Chinese context has both its claim and drawbacks. China is a fast developing state in which many individuals are pressured to work long hours and suffer from a substantial amount of piece of work-family conflict. Thus, it is most fruitful to understand the touch on of piece of work-family unit practices on reducing work-family unit conflict in this context. This study also provides a cross validation of the constructs that were previously used in the Western context. Nevertheless, the specific contextual differences between Cathay and Western countries may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Thus, a cantankerous-cultural comparative report is called upon.

Conclusion

This current research investigates the relationship betwixt employees' perceived work-family practices (including two dimensional configurations of "employee and family unit care" and "piece of work flexibility") and employee work-family disharmonize. It also examines the role of claiming stress and hindrance stress as moderators. By surveying 841 ceremonious servants in Beijing, nosotros found that practices of work flexibility have a more salient effect in reducing work-family conflict, and that both types of work stress increased work-family conflict. In addition, challenge and hindrance stress differentially moderated the relationship between perceived piece of work-family practices and work-family conflict. Loftier challenge stress consistently helped to strengthen the effectiveness of work-family residuum practices in reducing work-family unit conflict, while high hindrance stress constrained the effectiveness of piece of work-family unit practices on work-family disharmonize. This provides additional insight into the management of work-family unit interface and ideas for future research.

References

-

Aiken, L. S., & West, Due south. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, California: Sage.

-

Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E., Bruck, C. South., & Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future inquiry. Journal of Occupational Wellness Psychology, 5(2), 278.

-

Allen, T. D., Johnson, R. C., Saboe, K. N., Cho, E., Dumani, S., & Evans, South. (2012). Dispositional variables and work-family conflict: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Beliefs, lxxx(1), 17–26.

-

Anderson, S. E., Coffey, B. Due south., & Byerly, R. T. (2002). Formal organizational initiatives and informal workplace practices: Links to piece of work-family conflict and chore-related outcomes. Journal of Management, 28(6), 787–810.

-

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Periodical of the academy of marketing scientific discipline, xvi(one), 74–94.

-

Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., & Nassen, K. D. (1998). Representation of measurement error in marketing variables: Review of approaches and extension to three-facet designs. Journal of Econometrics, 89(1), 393–421.

-

Beauregard, T. A., & Henry, L. C. (2009). Making the link betwixt work-life balance practices and organizational performance. Human Resources Management Review, 19(ane), 9–22.

-

Beham, B., & Drobnič, Due south. (2010). Satisfaction with piece of work-family balance among German role workers. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(half-dozen), 669–689.

-

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the assay of covariance structures. Psychological bulletin, 88(three), 588.

-

Berg, P., Kalleberg, A. 50., & Appelbaum, E. (2003). Balancing work and family: The role of high‐commitment environments. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Social club, 42(2), 168–188.

-

Bloom, North., Kretschmer, T., & Van Reenen, J. (2011). Are family-friendly workplace practices a valuable house resource? Strategic Management Journal, 32(iv), 343–367.

-

Bloom, N., Kretschmer, T., & Van Reenen, J. (2006). Work Life Balance. Management Practices and Productivity. Working Paper, Stanford University

-

Brough, P., O'driscoll, M. P., & Kalliath, T. J. (2005). The power of 'family unit friendly' organizational resources to predict work–family conflict and chore and family satisfaction. Stress and health, 21(4), 223–234.

-

Byron, K. (2005). A meta-analytic review of work-family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 169–198.

-

Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. Yard., & Williams, Fifty. J. (2000). Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work-family conflict. Periodical of Vocational Behavior, 56(2), 249–276.

-

Cavanaugh, 1000. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. Five., & Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among United states managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(1), 65.

-

Christensen, K. Due east., & Staines, G. L. (1990). Flextime: A viable solution to work/family disharmonize? Journal of Family Issues, eleven(iv), 455–476.

-

Conway, J. K., & Lance, C. E. (2010). What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational enquiry. Periodical of Business and Psychology, 25(iii), 325–334.

-

de Blossom, J., Geurts, S. A., Taris, T. Due west., Sonnentag, S., de Weerth, C., & Kompier, Chiliad. A. (2010). Effects of vacation from work on health and well-being: Lots of fun, chop-chop gone. Work & Stress, 24(2), 196–216.

-

Den Dulk, L., Peper, B., Černigoj Sadar, N., Lewis, S., Smithson, J., & Doorne-Huiskes, V. (2011). Work, family unit, and managerial attitudes and practices in the European workplace: Comparison Dutch, British, and Slovenian fiscal sector managers. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Lodge, 18(2), 300–329.

-

Drobnič, Southward., & León, M. (2014). Bureau freedom for worklife balance in Germany and Spain (Worklife balance:The agency and capabilities gap). Oxford and New York: Oxford Academy Press.

-

Friedman, D. East. (1990). Corporate responses to family needs. Marriage & Family Review, xv(ane-2), 77–98.

-

Friedman, D. East., & Galinsky, E. (1992). Work and Family unit Problems: A Legitimate Concern. In Due south. Zedeck (Ed.), Work, Families, and Organizations (pp. 150–78). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

-

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family unit conflict: Testing a model of the work-family unit interface. Periodical of Applied Psychology, 77(1), 65.

-

Gajendran, R. S., & Harrison, D. A. (2007). The expert, the bad, and the unknown near telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1524–1541.

-

Goff, Due south. J., Mountain, Thou. G., & Jamison, R. L. (1990). Employer supported child care, work/family conflict, and absence: A field study. Personnel Psychology, 43(four), 793–809.

-

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family unit roles. Academy of Direction Review, ten(1), 76–88.

-

Grzywacz, J. G., & Marks, N. F. (2000). Reconceptualizing the work-family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 111.

-

Invitee, D. (2002). Man resource management, corporate performance and employee wellbeing: Building the worker into HRM. The Journal of Industrial Relations, 44(three), 335–358.

-

Hammer, L. B., Neal, Chiliad. B., Newsom, J. T., Brockwood, Thou. J., & Colton, C. L. (2005). A longitudinal written report of the effects of dual-earner couples' utilization of family unit-friendly workplace supports on work and family outcomes. Periodical of Applied Psychology, 90(iv), 799.

-

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513.

-

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, fifty(three), 337–421.

-

Hobfoll, South. E., & Freedy, J. (1993). Conservation of resource: A full general stress theory practical to exhaustion. American Psychologist, 44, 513–523.

-

Hobson, B. (2014). Worklife balance. Oxford and New York: Oxford Academy Press.

-

Hobson, B., & Fahlén, S. (2009). Applying Sen'southward Capabilities Framework within a European Context: Theoretical and Empirical Challenges. REC-WP 03/ 2009. Working Papers on Reconciliation of Work and Welfare in Europe. RECWOWE Publication, Dissemination and Dialogue Middle, Edinburgh

-

Kahn, R. L., Wolfe, D. K., Quinn, R., Snoek, J. D., & Rosenthal, R. A. (1964). Organizational stress. New York, NY: Wiley.

-

Kelly, E. L., Kossek, E. E., Hammer, Fifty. B., Durham, Thousand., Bray, J., Chermack, Yard., Murphy, L. A., & Kaskubar, D. (2008). Getting in that location from hither: Research on the effects of work-family initiatives on work-family disharmonize and business outcomes. Academy of Management Annals, 2, 305–349.

-

Kinnunen, U., & Mauno, South. (1998). Antecedents and outcomes of piece of work-family disharmonize amid employed women and men in Finland. Human being Relations, 51(ii), 157–177.

-

Konrad, A. One thousand., & Mangel, R. (2000). The affect of work-life programs on firm productivity. Strategic Direction Journal, 21(12), 1225–1237.

-

Kossek, E. East., Lautsch, B. A., & Eaton, S. C. (2006). Telecommuting, control, and boundary management: Correlates of policy utilise and practice, job control, and piece of work-family effectiveness. Journal of Vocational Beliefs, 68(two), 347–367.

-

Kossek, E. Due east., & Ozeki, C. (1998). Piece of work–family Conflict, Policies, and the Job–life Satisfaction Human relationship. Periodical of Applied Psychology, 83(2), 139–149.

-

Kraut, A. I. (1990). Some lessons on organizational enquiry apropos work and family problems. Human being Resource Planning, 13(two), 109–119.

-

Lapierre, L. M., & Allen, T. D. (2006). Work-supportive family, family unit-supportive supervision, use of organizational benefits, and problem-focused coping: Implications for work-family unit disharmonize and employee well-being. Periodical of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(2), 169.

-

Lazarus, R. South., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer publishing company.

-

Lee, Southward., & McCann, D. (2006). Working time capability: Towards realizing individual choice. In J.-Y. Boulin, G. Lallement, J. Messenger, & F. Michon (Eds.), Decent Working Time: New Trends, New Issues. Geneva: International Labour Office.

-

LePine, J. A., LePine, Thou. A., & Jackson, C. L. (2004). Claiming and hindrance stress: Relationships with exhaustion, motivation to learn, and learning functioning. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(5), 883.

-

LePine, J. A., Podsakoff, North. P., & LePine, M. A. (2005). A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships amidst stressors and performance. Academy of Management Periodical, 48(5), 764–775.

-

Leslie, L. Thousand., Manchester, C. F., Park, T. Y., & Mehng, S. A. (2012). Flexible work practices: A source of career premiums or penalties? Academy of Management Periodical, 55(vi), 1407–1428.

-

Lewis, J. (1992). Gender and the development of welfare regimes. Periodical of European social policy, two(3), 159–173.

-

Liao, H., Toya, Grand., Lepak, D. P., & Hong, Y. (2009). Do they run into eye to center? Management and employee perspectives of high-functioning work systems and influence processes on service quality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(two), 371.

-

Madsen, S. R. (2003). The effects of dwelling house-based teleworking on work-family conflict. Human Resource Evolution Quarterly, 14(one), 35–58.

-

Maertz, C. P., Jr., & Boyar, S. Fifty. (2011). Work-family unit conflict, enrichment, and residual under "levels" and "episodes" approaches. Journal of Management, 37(1), 68–98.

-

Neal, M. B., & Hammer, L. B. (2007). Working couples caring for children and crumbling parents: Effects on piece of work and well-being. Lawrence Erlbaum Assembly Publishers.

-

O'driscoll, K. P., Poelmans, Southward., Spector, P. E., Kalliath, T., Allen, T. D., Cooper, C. L., & Sanchez, J. I. (2003). Family unit-responsive interventions, perceived organizational and supervisor support, piece of work-family disharmonize, and psychological strain. International Periodical of Stress Management, x(four), 326.

-

Pelled, L. H., Eisenhardt, K. M., & Xin, K. R. (1999). Exploring the black box: An assay of work group diversity, conflict and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(1), 1–28.

-

Perry-Smith, J. E., & Blum, T. C. (2000a). Work-family human resource bundles and perceived organizational performance. Academy of Management Journal, 43(vi), 1107–1117.

-

Perry-Smith, J. East., & Blum, T. C. (2000b). Work-family human resource bundles and perceived organizational performance. University of management Journal, 43(6), 1107–1117.

-

Pfeffer, J. (1981). Management as symbolic action: the creation and maintenance of organizational paradigms. In B. G. Staw & L. Fifty. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior. Greenwich, CT: JAI Printing.

-

Podsakoff, N. P., LePine, J. A., & LePine, M. A. (2007). Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. Periodical of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 438.

-

Premeaux, Due south. F., Adkins, C. L., & Mossholder, G. Due west. (2007). Balancing piece of work and family: A field study of multi-dimensional, multi-function piece of work-family disharmonize. Journal of Organizational Beliefs, 28(6), 705–727.

-

Rothbard, Northward. P. (2001). Enriching or depleting? The dynamics of date in work and family roles. Authoritative Science Quarterly, 46(4), 655–684.

-

Scherer, Southward., & Steiber, N. (2009). Piece of work and Family in Conflict? The Bear on of Work Demands on Family Life. In D. Gallie (Ed.), Employment regimes and the quality of work (pp. 137–178). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

-

Schieman, Due south., Glavin, P., & Milkie, Thou. A. (2009). When piece of work interferes with life: Work-nonwork interference and the influence of work-related demands and resources. American Sociological Review, 74(half-dozen), 966–988.

-

Selye, H. (1976). Forty years of stress research: Chief remaining problems and misconceptions. Canadian Medical Clan Journal, 115(1), 53.

-

Shockley, Thou. Thousand., & Allen, T. D. (2007). When flexibility helps: Another look at the availability of flexible work arrangements and work-family conflict. Periodical of Vocational Behavior, 71(3), 479–493.

-

Smith, Due south. R., Hamon, R. R., Ingoldsby, B. B., & Miller, J. Due east. (2008). Exploring family theories. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

-

Staines, G. Fifty. (1980). Spillover versus compensation: A review of the literature on the relationship between work and nonwork. Human Relations, 33(2), 111–129.

-

Steiber, N. (2009). Reported levels of time-based and strain-based conflict between work and family roles in Europe: A multilevel approach. Social Indicators Research, 93(iii), 469–488.

-

Thompson, C. A., Beauvais, L. L., & Lyness, K. South. (1999). When work–family benefits are non enough: The influence of work–family culture on benefit utilization, organizational attachment, and work–family unit conflict. Journal of Vocational behavior, 54(3), 392–415.

-

Thompson, C. A., Thomas, C. C., & Maier, M. (1992). Work–family unit disharmonize and the bottom line: Reassessing corporate policies and initiatives. In U. Sekaran & F. T. Leong (Eds.), Womanpower: Managing in times of demographic turbulence (pp. 59–84). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

-

Valcour, K. (2007). Work-based resources as moderators of the relationship between work hours and satisfaction with work-family rest. Journal of applied psychology, 92(6), 1512–1512.

-

Voydanoff, P. (2005a). Consequences of boundary-spanning demands and resources for work-to-family unit conflict and perceived stress. Journal of occupational health psychology, x(4), 491.

-

Voydanoff, P. (2005b). Toward a conceptualization of perceived work‐family unit fit and residue: A demands and resources approach. Journal of marriage and family, 67(four), 822–836.

-

Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical word of the structure, causes and consequences of melancholia experiences at work. In B. M. Staw & 50. L. Cummings (Eds.), Inquiry in organizational behavior. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported past the National Natural Science Foundation of Prc (Project no. 71372003), and the Fundamental Inquiry Funds for the Key Universities and the Research Funds of Renmin University of Mainland china (Grant no. 15XNL023).

Authors' contributions

Xc carried out model building and drafted the manuscript. YZ participated in the theory structure and designed the written report. CW participated in the design and performed the statistical analysis. CPH participated in implication construction and coordination. All authors read and approved the concluding manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they accept no competing interests.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided y'all give appropriate credit to the original writer(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Chang, X., Zhou, Y., Wang, C. et al. How do work-family unit balance practices affect work-family unit disharmonize? The differential roles of work stress. Front. Bus. Res. China 11, 8 (2017). https://doi.org/x.1186/s11782-017-0008-iv

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s11782-017-0008-4

Keywords

- Work-family residual practices

- Work-family conflict

- Claiming stress

- Hindrance stress

rollinsandelibubled.blogspot.com

Source: https://fbr.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s11782-017-0008-4

0 Response to "Researchers Have Found That Family Management Practices Are Positively Related to"

Post a Comment